At the Thursday evening Penzance Cornish Session at the Admiral Benbow we often hear from people listening, “it sounds Irish. I didn’t realise Cornwall had its own music” or “it sounds really similar to Scottish music, I can hear a lot of similarities.”

It’s easy to see why many people may walk into a Cornish session and think it Irish. Many of the instruments we regularly play are the same: fiddles, concertinas, melodeons, accordions, whistles and recorders, sometimes clarinets, occasional flutes, (open back) banjos, mandolins and bouzoukis. Although drums make an occasional appearance percussion such as bodhráns are not common at Cornish sessions. Harps are rare compared with, say Wales. Guitars tend to be in the minority and usually provide rhythm and accompaniment. Although brass bands are a significant part of Cornish musical culture brass instruments are not often heard playing Cornish traditional tunes, you might hear the odd saxophone or tuba as part of a dance or processing band.

The general sound of that combination of acoustic instruments playing jigs, reels (more likely to be furries in Cornwall), hornpipes (few strathspeys although these were popular for a time for Cornish dancing in the 18th and 19th centuries), polkas, marches, waltzes, slow airs will strike a similar chord (if you’ll pardon the pun) to the uninitiated. Together with the common keys of the music, the most popular being G and D major, A, E, D and G minor, plus a few in modal keys that ‘trad sound’ will be familiar.

Some musicians reply that the similarities are because Cornish music is all part of the wider modern Celtic musical tradition (which it is) and thus the similarities. Some of the tunes we play have variations in Ireland, Scotland, America, Canada and even England but we think there are more subtle aspects to our repertoire that distinguish it from those traditions.

The Cornish Trad repertoire is a happy combination of contemporary and historical, varied in style and playability. Cornish music has not fossilised. Modern tunes are composed with the tradition in mind, many connected to the memory and feeling of a feature, person or place of import, and those that have become accepted and widely played fit in pretty indistinguishably from some older tunes. A popular pair of tunes at the Penzance Cornish Session is Newlyn Fair and Bernard’s Polka, composed by Marc Cragg. They are also performed for processing and dancing too.

Playing style

The Cornish Trad sound is less reliant on a fixed set of ornaments and tricks than, say Irish or Scottish trad. Rolls and fast triplets that characterise Celtic jigs and reels are used but are much less common and employed perhaps more sparingly. The characteristic ‘scotch snap’ that makes strathspeys so attractive to play and listen to is something particular to the traditions which have a much greater repertoire that needs them. What you will hear from Cornish fiddlers, box and string players is double-stopping, drones and occasionally harmonies and counter melodies, sometimes learned, sometimes improvised. Most session players will play a tune ‘straight’ with occasional ornamnentation. Fiddlers, for example, will employ grace notes, trills or mordents to emphasise and decorate. We also tend to play with more dynamic range, with softs and louds and contrast to suit the mood of a tune or set.

Contrasting speeds

Speed really depends on the context in which a tune is played by an instrumentalist. We may play jigs slower when dancers are dancing to them, but go full pelt during a session or band performance. We may speed up tunes that others play as a march (for example processing bands) and turn them into fast reels. We’ll usually play polkas fast with good emphasis on the off-beats. In contrast our waltzes may be played quite slowly, almost like slow airs, or some 3/4 sets may be played more quickly to create the kind of whirl that people enjoy hearing waltzes. Much depends on mood and who’s playing. What you will certainly find in any Cornish session is a lot of contrast in speeds which show off the wide range of tune types we play.

Some tunes we play will accelerate each time through, for example Newlyn Reel and King of Sweden, both tunes that are usually danced to with each time getting a bit faster. I wish these had a name – getting faster tunes sounds a bit clumsy – if you know what they are called or even the dances let us know.

Contrasting rhythms

Cornish tunes don’t all easily fit set categories and below I have used a pragmatic approach to categorising tune types for the sake of this exercise. Really it is just to demonstrate the wide range of rhythms we play. The tunes I class as reels are 4/4 tunes that we play fast with few or no pauses or long notes or big changes of rhythm. The tunes I class as furries are 4/4 tunes particular to Cornish dances (sometimes also called jowster tunes at nos lowen events), will be no more than 16 bars, usually (not always) with one A part and one B part of equal measure. Then we also have 4/4 marches, played more gently with more changes in pace even within tunes, sometimes played with swing, and 4/4 hornpipes with dotted or swung rhythm throughout, fast enough to dance to but not so fast as to make people fall over.

Song melodies

Many of our instrumental tunes derive from songs, such as Ryb an Avon, Warleggan Ox Driver and Nine Brave Boys. We’ve even taken the tune from the recently discovered song Can Palores for just this purpose. This came about because of the major influence Dr. Ralph Dunstan’s two song books has had since he published them in 1929 (Cornish Song Book Lyver Canow Kernewek) and 1932 (Cornish Dialect and Folk Songs). Before Dunstan, Sabine Baring-Gould’s Songs of the West, 1890, also providing a rich hunting ground for tunes which also had words associated with them. Following these publications and their circulation at Cornish gatherings Dr. Merv Davey’s song and tune research in the 1970s to 1990s produced further tunes that had songs associated with them, many of the published in Hengan.

Dance music

The other major influence on the sound of Cornish Trad are tunes intended for dancing. This has also dictated (or been derived from) the length of tunes e.g. 16 bar furries. Five-steps or kabm pemp are relatively new creations that have nonetheless had a serious impact on Cornish traditional music. These are tunes to be played briskly in 5/4 time to accompany nos lowen dancing, similar to Breton dancing. The tune describes the rhythm with emphasis usually (not always) on beats 1 and 4 to match the footwork. You won’t find five-steps like these in other British musical traditions.

Let’s take a look at the Penzance Cornish Session set list to analyse what we are playing and therefore what it might sound like.

Repertoire and sets

Currently we have 86 tunes in Penzance Cornish Session’s repertoire and most of them are played in sets of 2, 3, 4 and even 6 (the fab furries). Tune sets might include a change of key, a change of rhythm and/or a change of speed. Sets of tunes help create excitement and anticipation in the listener and this is a method we can really go to town on to put our own stamp on our musical tradition. Change of pace examples are a slow An Dyfunyans (The Awakening) followed by pacy polka Ewon an Mor (meaning sea foam) and slow jig An Diberdhyans (The Parting) followed by Dons Bewnans (meaning Dance of Life) played as a reel. Our jig sets use key changes to create interest, e.g. Falmouth Gig set goes from D to G to D, and Hernen Wyn set goes from Em to D to Em.

Our repertoire is divided into 11 tune types according to my rudimentary classification (i.e. the descriptions that work best for us as musicians). We also have a small handful of tunes that don’t fall into easy categorisation so we don’t bother. By number, most of our tunes are 6/8 jigs, followed by furries and waltzes. Hornpipes, reels and polkas are more or less equal. We like our slow airs, sometimes sung along with being played, e.g. Warleggan Ox Driver and O What is That Upon Thy Head. The one strathspey is Cock in Britches which some play as a hornpipe but I prefer to keep its snap, that’s how it’s danced to as a broom dance. The mazurka is Turkey Rhubarb which has many variants under different names all over the world but ours has become peculiar to west Cornwall.

Keys

Analysing the keys of our current repertoire was a fascinating exercise. Two-thirds of our repertoire is played in a major key, with G and D dominating and a couple in F and C. I think this has a lot to do with the influence box players have had on Cornish Trad music. When you look at the historical instrumental repertoire the story is very different with Bb, F and C accounting for far more tunes, probably reflect the dominance of the fiddle and fifes, and of course, those keys being common for sung tunes. Just under one-third of our tunes are in a minor key, here we have more variation with Em being the most popular. We also play a few modal tunes, and arguably some of the minor key tunes are/were modal judging by accidentals and have used concert pitch keys to standardise them for communal playing.

Proportion of repertoire by key

Proportion of repertoire by tune type

Era

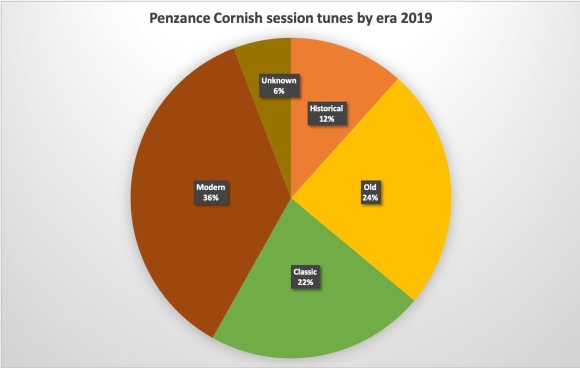

If the above isn’t enough to convince you that the sound of Cornish Trad is both varied and full of musical interest, let’s take a look at the eras that our traditional tunes come from. Some people really think that Cornish music is a modern invention but the evidence from the tune collection of Penzance Cornish Session, and indeed the wider wealth of Cornish Trad tunes, would suggest otherwise. Let me explain the terms I use to divide tunes into different periods. These categories are not set in stone, they just help us (me) better understand what we’re playing.

- Historical. Recorded or known by the 18th century

- Old. Recorded or known by the 19th century

- Classic. Recorded or known by the 20th century

- Modern. Composed for the tradition after 1990

- Unknown. Unclear origins.

About one-third of our repertoire comprises modern tunes. These are tunes composed by identifiable people after 1990 specifically for the tradition (I call this the Racca period, the major project to bring together music specifically for the purpose of Cornish bands, sessions and events). Nearly 50% of our tunes are Classic (20th c.) or Old (19th c.). Some of those may even have been in circulation much earlier, it’s just the era in which they were notable enough to be recorded in collections of songs or tunes or otherwise recorded from living memory.

12% of our repertoire, probably uniquely among Cornish sessions, are from the historical period, that of the 18th century and before. We are great fans of Mike O’Connor’s work on Cornish musical manuscripts and want to bring these tunes that were enjoyed at Cornish country houses and special events, into the repertoire. A small percentage of tunes we just don’t know how they got into our books, but I guess that’s folk music for you!

Cornwall is not an island

To conclude this post on what Cornish music sounds like, I’d like to remind readers that Cornwall is not, and certainly has never been, an island. Until the 1940s Cornwall was at the centre of global maritime commerce and transport. Traditional music will not obey modern political and administrative boundaries and so the search for pure Cornish tunes is probably futile (although in some cases we really cannot find any variations, relatives or similar tunes elsewhere) and equally futile is denying that a distinctly Cornish tradition of music exists, being either just a modern invention, or just part of an English tradition. No one has ever told us our session sounds like English music!

I would expect our repertoire to be magpie-ish. We are not far from Ireland and the other regions of the Atlantic highway. People come and go in maritime communities, some of them stay and become part of more static agricultural communities of the interior. Newlyn Reel, a tune and dance popularised by Newlyn fisher folk, sounds awfully like a polonaise from Eastern Europe, and why not? For me that kind of thing is typically Cornish, being open to outside influences and making them our own.